A Semi-Automatic Rivet Embossing Machine.

Most railroad locomotives and

rolling stock as well are festooned with rivets. When scratch building

these can duplicated in a variety of ways. Probably the easiest is just

to emboss them onto a piece of thin styrene and overlay it onto the

surface that needs rivets. Other options include gluing small diameter

slices of styrene rod on the surface, placing small drops of glue on the

surface or drilling holes and inserting pins or track nails. All of

those are pretty labor intensive and while OK for applications where

only a limited number are needed or they are located in areas that would

be difficult to do using the embossing method. There are also water

slide decals that come with glue dots applied to them that can be

applied in strips and some modelers have had success using them but you

do have the issue of the decal film which is best used over a glossy

surface and it can be difficult to totally hide the clear decal film.

An

example of using pin heads for rivets can be seen in the photo below.

Because the rivets needed to be placed in a narrow area along a piece of

'Z' shaped styrene it was not possible to emboss them. Due to the number

required adding the rivet detail consumed most of the time required to

build this car.

When

I started my standard gauge 0-6-0 project I knew one of the issues was

going to be rivets. The number required on the locomotive was not all

that excessive but the tender was another issue all together. The

drawing showed row after row of closely spaced rivets. The thought of

drilling and installing that many pins put me off big time and caused me

to go in search of other possibilities. One of the first things that

came to mind was a sewing machine. Here was device that had a part that

moved up and down and a mechanism for moving material in incremental

steps. The feed amount was variable to provide the required number of

stitches per inch. I had an old machine that had originally been my

wife's mother's and was passed down to her and then set aside when she

got a newer model.

I

started experimenting using a cut down and properly blunted needle.

Initially results were moderately encouraging. Obviously there would

need to be some sort of guide to keep the material going in a straight

line and to set the position for a line of rivets. The first issue I ran

into was that the styrene tended to slip resulting in unevenly spaced

rivets. The advance mechanism was designed to move cloth not slippery

plastic. Increasing the pressure on the hold down foot did not help

much. I also tried laminating some card board to the back of the styrene

or using different types of tape which helped some. Another issue was

that the area below the needle was a hole to allow the needle to drop

below the surface and pick up the thread on the bobbin. This meant there

was not much in the way of back up when embossing and resulted in a less

that distinct rivet shape. I ended up spending way too much time with

this and came to the conclusion that to make it all work would require

some serious modifications to the sewing machine with no guarantee it

would work to my satisfaction in the end. A new plan was needed.

It

was then I decided to go back to my roots and try something from my

past. One of the first companies that I worked for after I mustered out

of the Air Force built systems for scanning materials being checked

using ultrasound. The accuracy for the positioning wasn't as critical as

that used in CNC machines and all that was required was a simple stepper

motor drive. The technology back in those days (early 70's) was all

discrete components and logic circuits as micro processors were in their

early stages and quite expensive. Stepper motors are still being used,

generally not in high accuracy machinery but in less demanding

applications and are commonly found in hobbyist level 3D printers, laser

cutters, hobby craft cutters like the Silhouette and other things. The

difference today versus the way we did it back then was now everything

is modular and computer controlled. The stepper motor drivers are

designed to receive inputs from computers. That was a bit of a stumbling

point for what I had in mind. Software is available that can be run on a

laptop to provide the necessary step increment to the stepper motor but

one needs to spend time learning the program and I didn't want to tie up

my laptop. Likewise one no doubt could use something like a Raspberry Pi

or Arduino with the proper programming and accomplish the same thing but

again there is that learning curve and at my age it was something I

didn't want to invest the time in just for one project.

Fortunately

some of the logic circuits from back in the day are still available and

I decided I would return to my roots and build my own pulse sequencer

using discrete components. Note: all of this at this point is only to

build an indexer to move the material to be embossed in precise and

consistent increments. I also realize this will be of limited interest

to most modelers but I'm putting it out here anyway.

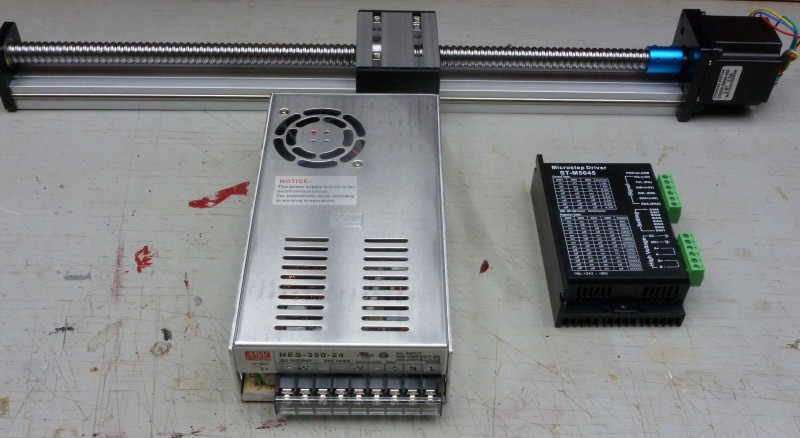

First

lets look at the hardware involved. The first piece of the puzzle is a

linear slide shown in the photo below.

This

is a precision device. It consists of an aluminum extrusion with a steel

rod inserted in each side which protrudes far enough to engage the

rollers on the movable portion. The screw which runs from a bearing

plate at the left end to the ball bearing stepper motor at the other end

is similar to a acme type thread and is referred to as a ball screw. The

groove in the screw is sized to ball bearings which are enclosed in a

spiral track inside the ball nut which is attached to the underneath

side of the movable carriage. This ball nut is preloaded which means

that when it is screwed on ball screw the ball bearings are pressed

tightly into the grooves providing a very precision fit with very little

if any backlash. The screw has five threads per inch, this will figure

into the math later on. I've already mentioned the word stepper motor a

couple of times and for those not familiar with them you can find a

better definition here

than I can offer and includes an animated figure to illustrate how it

works as well. The stepper motor I'm using makes a 1.8º of rotation each

time the coils are are pulsed and therefore it requires 200 pulses to

make one rotation. (1.8º x 200 = 360º)

Now

for the math part. 200 pulses will rotate the ball screw 1 turn and with

5 threads per inch the screw will move the slide 1/5 of an inch or

.200". Therefore each pulse sent to the motor will index the slide

.001". Now all that is required is a circuit that will send the correct

number of pulses to move the slide the amount you want between rivets in

thousands of an inch when triggered. Is any of this making sense ? I

hope so, it's not rocket science.

Two

other pieces of the puzzle are shown in the next photo.

The

item on the left is a regulated 24V DC switching power supply. This will

supply the power required by the motor and it's driver. It will also be

regulated down to provide power to the logic circuits needed to generate

the pulses. The device on the right is the modular motor control. It

takes the pulses from the logic circuit and drives the coils in the

motor to provide the stepping function. The unit is universal and

designed to drive a variety of different size and step angle motors, the

charts printed on the side show the positions for programming switches

on the connector side of the module. The module also accepts commands to

determine the direction of rotation, provides inputs for jogging the

motor to the initial starting position and provides stop functions that

can stop the motor when a limit has been reached.

To

date these three pieces have been tested. A square wave generator was

bread boarded to provide a constant stream of pulses to the driver

module which allowed me to run the slide back and forth and everything

so far is working as advertised. The next chore will be to bread board

the logic circuit which will read a set of thumb wheel switches. These

will be set for the index required in thousands of an inch and supply

that number of pulses to the motor driver when triggered to do so.

The

next update will be published when I have finished bread boarding and

tested the logic circuit and at that time I will go into how this will

be tied into the parts that will do the actual embossing.

Updated

3/10/19